What do zoning and software have in common? What does either contribute to city fragility?

They both create outcomes based on codes. While software lends itself to rapid iteration, testing, and debugging, zoning often produces unintended consequences literally set in stone.

While the parallels are far from perfect, it’s instructive to compare the two. Many innovations come from comparing or combining two things we don’t normally think to do.

While I realize this is oversimplifying, the main software paradigms I’d like to compare are object-oriented and functional. The main zoning paradigms are currently euclidean and form-based.

Object-oriented programming is essentially writing software so that you have reusable blocks that control the state of an application. Functional programming uses math functions so that you don’t worry about the state. The main advantage is that you don’t have conflicts with state changes. The best explanation I’ve seen is Michael Feathers’ tweet:

“OO makes code understandable by encapsulating moving parts. FP makes code understandable by minimizing moving parts.”

Check the Programming Paradigms Wikipedia article for more details.

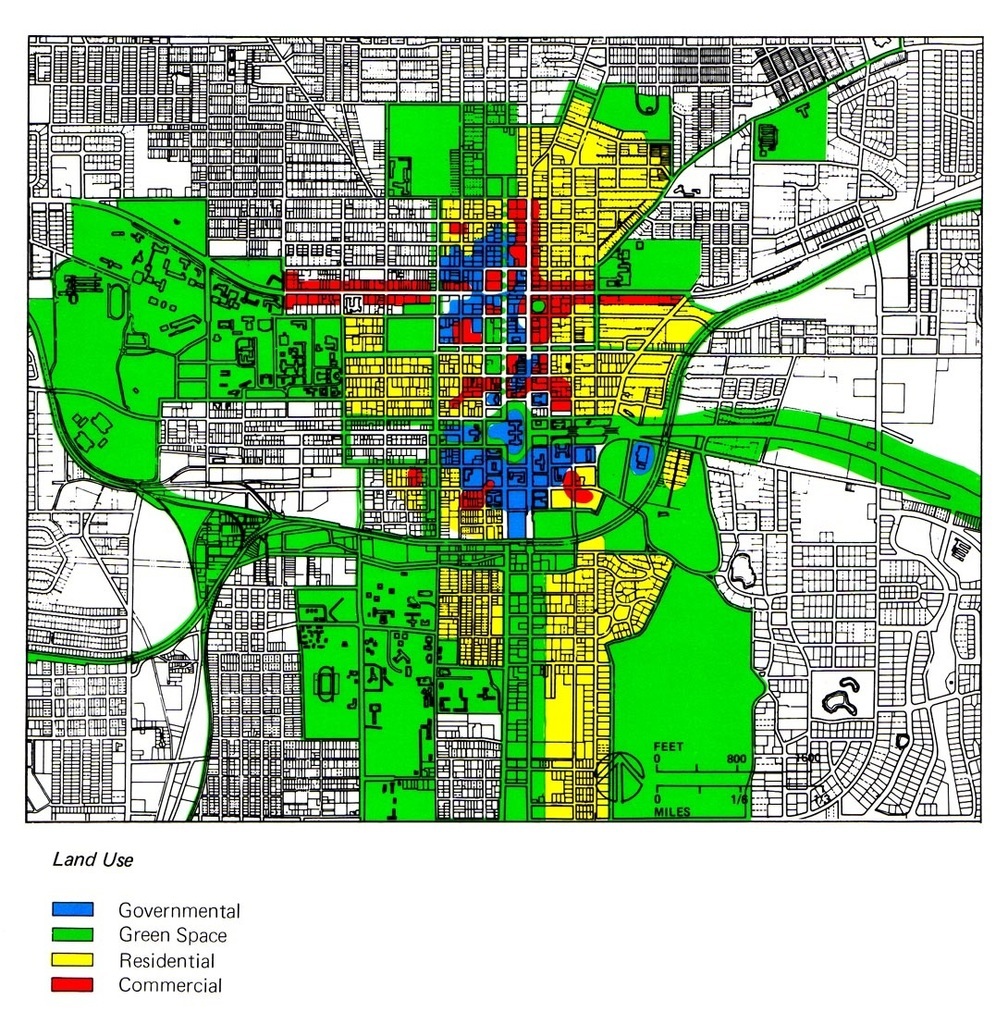

Euclidean zoning is what most cities have (see Tallahassee below). We call it Euclidean because it’s mostly about distance measurements. It essentially breaks up land according to use – residential here, industrial there. Back when the main concern was to move smoke stacks away from residential areas, it made sense. Now, not so much. Instead, in many places, we’ve separated our uses so much that we are completely dependent on cars to take us back and forth between them.

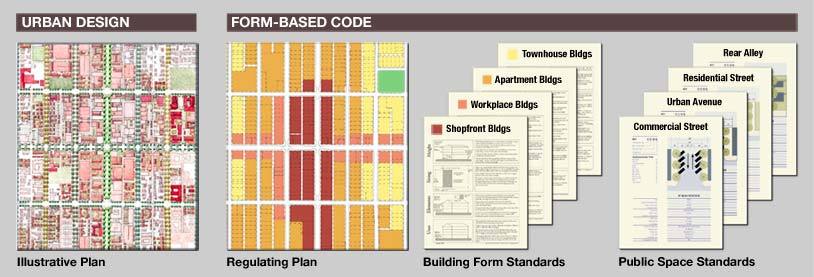

Form-based codes (see below) are the current reformation trend in zoning. Instead of saying how you use a property, now we’re saying what the property should generally look like. We realized treating buildings as stand-alone objects on their parcels destroyed the urban fabric.

Is urban fabric just an aesthetic choice? No, and here’s why. Many metrics of well-being are associated with community and walkability. Spending most of our lives in chairs, cars, and beds leads to shorter lifespans and less community interaction (social media excepted). Urban fabric can promote or discourage walking and community.

I’m not sure who said it first but all the Live, Work, Play developments we’ve been building have turned into Commute, Work, Netflix. Our urban environment and technology have changed our social interactions even though our evolutionary need has not changed. That’s why so much of American society is segmented, isolated, lonely, angry, struggling, etc.

That’s why if you had to pick one metric to base zoning on, you should probably pick walkability. A close second would be financial viability but walkability generally supports that outcome too.

Both of these zoning approaches lead us to fixed outcomes. You can calculate exactly what will be allowed to be built. The disconnect between planners and developers is that much of what is planned can’t be built from a financial feasibility standpoint. And many economic development departments end up looking smart when all the credit should go to changing demographics that they had no input into.

Cities are not fixed quantities. The question is then, what system of zoning wouldn’t require us to reform it 20-50 years later? Let’s assume that the point of zoning is to build strong towns and strong communities rather than keeping planners employed. What would give us that outcome?

In comparing software and zoning, I’m going to err on the side of utility rather than accuracy. If you’re a software developer, please go with me on this.

You might be inclined to think I was going to use this word analogy:

Euclidean Zoning : Form-Based Codes ::

Object-Oriented Programming : Functional Programming

We could say that Euclidean Zoning creates objects of residential zones, commercial zones, etc. And then Form-Based Codes don’t have those moving parts. While I think that comparison has merit, I think there’s a better fit:

Euclidean Zoning : Form-Based Codes : Something better ::

Machine Level Code : Object-Oriented Programming : Functional Programming

Machine level code and what came before object-oriented were tedious and explicit compared to object-oriented. I feel Euclidean Zoning is closer to that. There is no consistency from city to city with Euclidean Zoning. Yes, you can look at an area zoned single family and say you could only build single family but then you have to look at all the details such as any requirement (fixed or variable) for setbacks, materials, whether up to 4 units are specifically excluded, accessory structures, accessory dwelling units (e.g. tiny houses) and so on. You generally can’t know what the buildings have to look like without reading through most of the code.

In places with Euclidean Zoning, smaller developers are at a comparative disadvantage because working with the city to get something built can become a full-time role. Large developers can have a professional on staff to handle that.

Form-Based Codes are then compared to Object-Oriented Programming. Both create reusable objects. While you still need to read most of the code to understand the building forms, they are sometimes easier to read. Many places adopting form-based codes use the same form so going from place to place, you’re more likely to get what you expect.

The most interesting comparison to me is what we would get from a functional approach to zoning. Rather than having to go back and learn the entire syntax before you could understand what is happening, you could look at the surrounding parcels and eyeball what could come next. For the previous zoning paradigms, you look around and see that you can build more of what you already have. A functional paradigm could let our cities develop in a more incremental way.

There has been some discussion regarding “dynamic zoning” which could be the next iteration of zoning paradigms. For Dynamic Zoning, zoning is determined by the local context in terms of density. A couple of articles have been written about it at Strong Towns and Planetizen. Dynamic Zoning would allow the flexibility for the density to change incrementally.

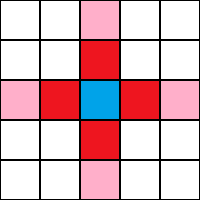

To extend the Dynamic Zoning theory, we could introduce a cellular automata model (see image). That would look at a certain number of parcels within a certain radius. The Strong Towns article suggested using city blocks. I suggest using a walking radius. Maybe 100 meters would be good since most people can visualize that much as a football or soccer field length.

We would need to bound the radius by features such as highways, rail lines, and rivers for example. We might want to make exceptions for new rail stops. Although, an incremental approach would likely have us put rail stops where they’re needed rather than where it’s politically expedient for cities or developers can make the most profit.

We would need to run some simulations to see the effect of such a zoning system. But if it looked promising, I would run a trial the way they do with special economic zones. The main difference I would add to the discussion is that zoning changes should probably be automated and monitored by city officials, not forced to go through a formal process.

I’d say revision and updates should take place automatically so that a developer would know what the zoning would be based on the current and future states. It shouldn’t depend on the city to grant the next increment of zoning density. It should be “by right” so that developers could start making longer-term plans and investments. When we say we want fewer moving parts, we have to ask “for whom”? If we want resiliency and anti-fragility, then we need easier adaptability. It’s primarily the developers that adapt the built environment.

Even then, we’re using density as the main metric. While that could be an improvement over the status quo of arbitrary use-zones, I think we could do better if we measure by walkability. The core metric of walkability and underlying purpose of a city is to facilitate complex social interactions whether they be economic, social, recreational, civic, or other.

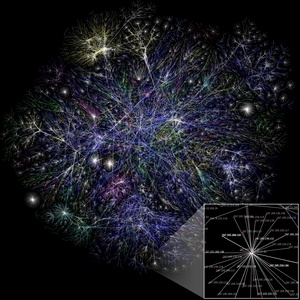

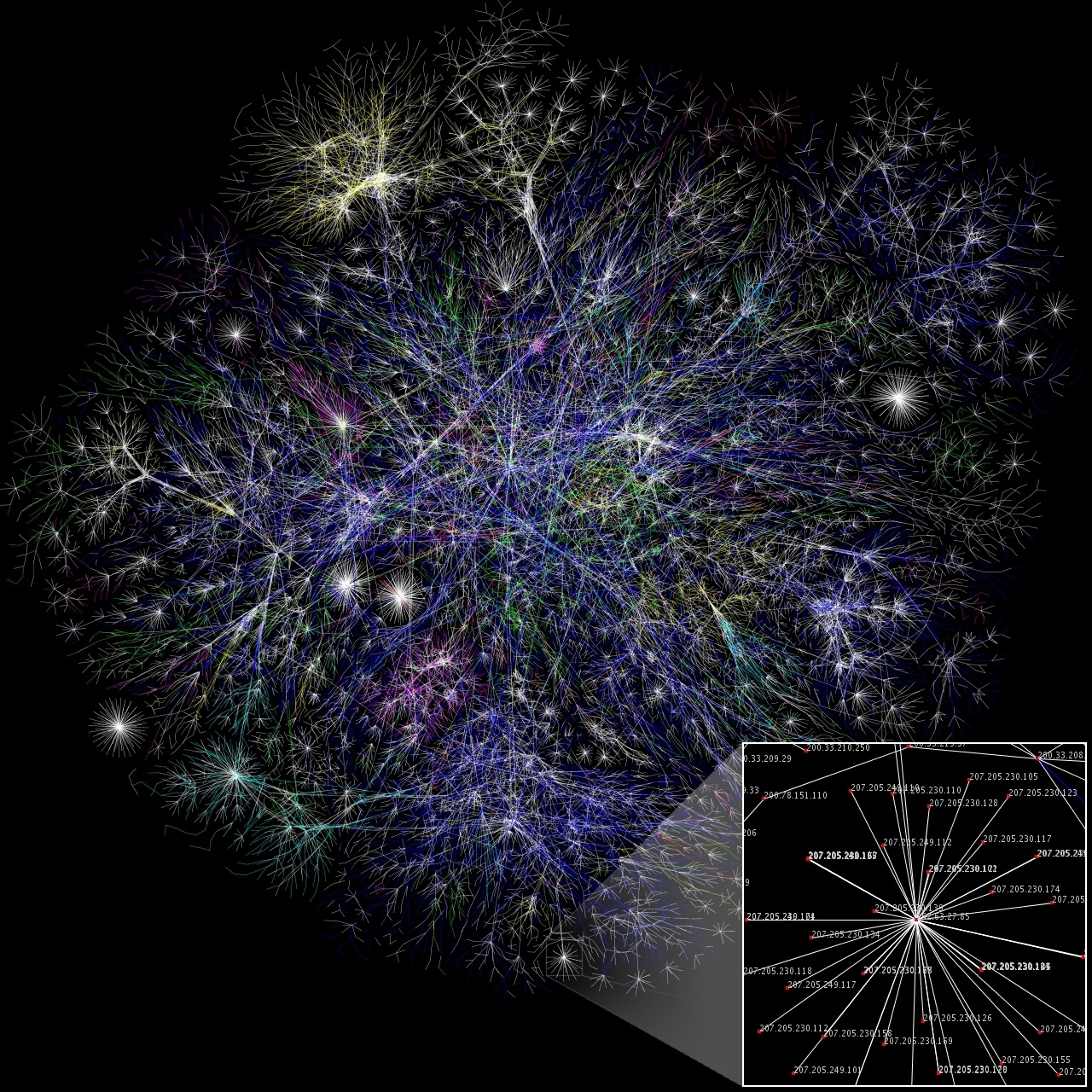

If we take walkability as our foundational metric, then we might propose an Interaction-Based Code. Rather than using a strictly Euclidean approach, we need to incorporate the underlying complexity as studied by network science (see image). In addition to measuring the density of commercial and residential units, we could measure the density of possible social and economic interactions between people and companies. How do the proposed forms and uses affect the diversity and density of the underlying socioeconomic network?

If we’re not asking that question, then we’re not measuring what matters long term. We’re baking-in structural fragility. And then we wonder why most of our corporate mixed-use developments don’t feel like real places.

In a future article, I’ll describe more in-depth the underlying urban socioeconomic network.

Leave a Reply