This article will describe the why, what, and how of Urban Prosperity Network (UPN).

UPN came out of my dissertation research. The motivating question was generally how to make better places and why we weren’t overall. The concept of “better” places is tricky of course because you have to have a metric to say how one place is better than another.

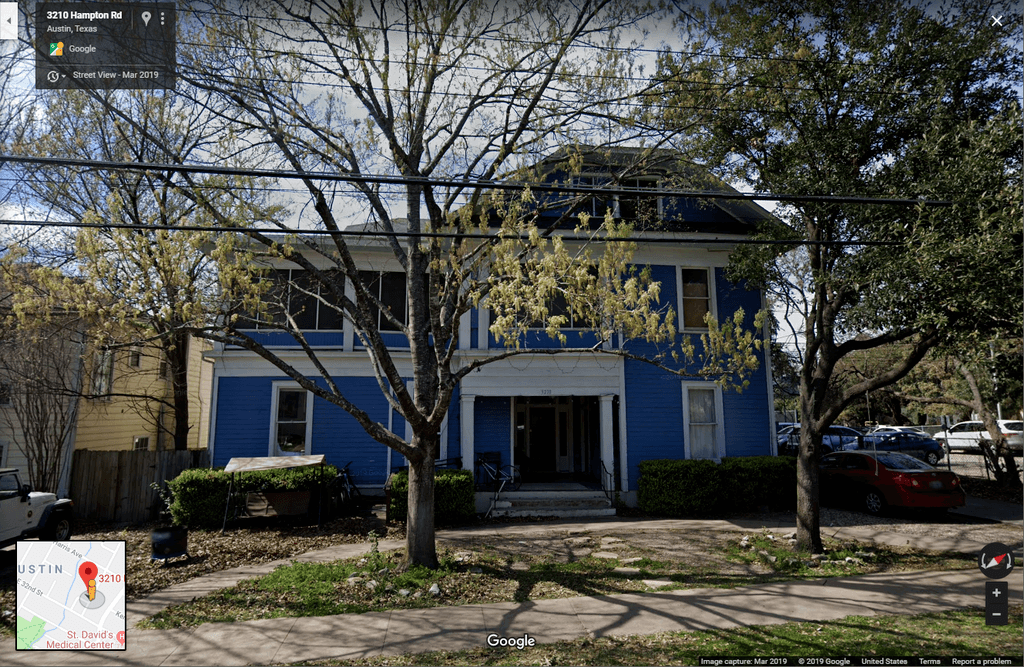

My background was that I had lived in quite a few different configurations, almost always with roommates, across countries and cultures including Mexico, Italy, Afghanistan, and India. I’ve visited a dozen or so countries besides. Since we started UPN, I’ve also lived in New Zealand. I lived in army barracks (Fig 1), a 3-story former brothel with 24 housemates (Fig 2), and built a tiny house (Fig 3). Most recently, I’ve lived in my own house and remodeled the floors, walls, attic, kitchen, and bathrooms (Fig 4).

Professionally, before going back to graduate school I had been many things including a Realtor, an Airborne Army medic, a middle school math teacher, and an online marketing freelancer.

Throughout my doctoral research, I kept looking for first principles. I knew that when we went for the highest and best use from the real estate perspective that profitability was the number one consideration. As much as I dislike admitting it, finance wins over design, especially in the built environment. I was aware of the triple bottom line of people, planet, and profits but the first two rarely make it on to proformas.

I ended up settling on wellbeing which can be pinned to public health outcomes associated with urban form. I landed on walkability as a proxy because it correlates with many of the same outcomes as wellbeing.

Speck states that for walking to happen in the public at large, a walk needs to be useful, interesting, safe, and comfortable. Having lived in Italy and India, I realized that walking occurred in those places even without some of those qualities. And having a real estate background, I knew there were legal and financial considerations in play as well.

Digging deeper, I found that my first principles became 1) cities exist to facilitate complex human interaction and therefore, 2) form follows social spaces (or should). Social interaction and their spaces include retail activity, employment, personal relationships, civic purposes, etc. I don’t have a citation for the first idea though I drew inspiration from Scale: The Universal Laws of Growth, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Pace of Life in Organisms, Cities, Economies, and Companies .

The second idea is an adaption of Christopher Alexander’s Pattern #205, “Structure Follows Social Spaces” . He states:

A first principle of construction: on no account allow the engineering to dictate the building’s form. Place the load bearing elements – the columns and the walls and floors – according to the social spaces of the building; never modify the social spaces to conform to the engineering structure of the building.

The idea is that if the purpose of our cities is to facilitate interactions, our built environment should be the containers for those interactions. Walking connects locations of social interaction. As-is, most of our built environment sequesters us, separates us, and requires us to use cars which come with a whole host of problems.

With those as first principles, we then tease out our values. The qualities that kept popping up in the literature and in my common sense were local autonomy and incrementalism.

By local autonomy I mean local ownership of residences and businesses. When you walk through a massive institutionally funded mixed-use development and you fell there’s something inauthentic about it – that’s usually what it is. Most of the time, no one there owns any part of it – not the renting apartment residents nor the renting national chain retail tenants.

Incrementalism means building things gradually over time rather than all at once to a finished state. Incrementalism can allow for greater flexibility when the market or needs change. The increment that is usually missing from cities is the Missing Middle buildings that exist between single-family houses and apartment buildings.

The year after I finished my dissertation I was working on a second dissertation. I opted not to complete that one but in my research, I came across a book called, When Brute Force Fails: How to Have Less Crime and Less Punishment . The author describes a way of using available resources and game theory to improve all areas by improving one area at a time.

I wasn’t able to find a word to describe this process so I made one up – dynamic concentration. You focus most of your resources on one area and then you have almost all your resources available to focus on the next area. City management and planning typically does the opposite – it distributes what little resources there are widely, fairly (hopefully), and insufficiently.

Dynamic concentration is different from triage as well. In medical triage, you separate casualties into at least three groups 1) those you can’t save with any amount of effort, 2) those you can save now, and 3) those you can save later. Triage is the process of prioritization. Dynamic concentration is the process of going about working on the most important part of group 2.

In the urban context, there are some places we can fix now, some that we can fix later, and some that we may never be able to fix. Rather than try to fix all parts of our cities at once, dynamic concentration says we need to reach a critical mass of walkable urbanism in one area before we try to bring it to another. I’ll elaborate on that in a future article.

For now, these are the three guiding principles of UPN:

- Local ownership

- Incrementalism

- Dynamic Concentration

Our aim is to educate the public in these principles through content creation, course development, game development, and real estate development. I summarize that as local community and economic development. That’s our contribution to making better places as a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit.

Leave a Reply